Afghanistan is the sixth country in the world impacted by climate change, and the country is changing negatively from a climatic perspective, according to Professor. Mohammad Daoud Shirzad, head of Kabul University’s Faculty of Environment.

He said that one of the reasons Afghanistan is experiencing drought is because of low and irregular rainfall that does not fall at appropriate times.

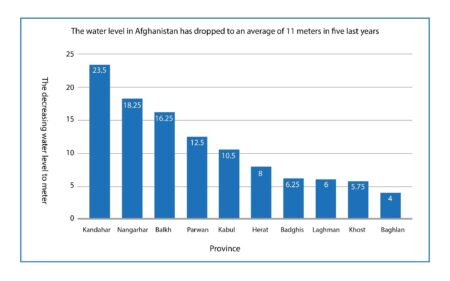

Shirzad added that the water level in Kabul, a heavily populated city with significant water use, has decreased to 11 meters in recent years.

“Sadly, this is a very serious deficiency of water. If it is not prevented, it will lead to another disaster,” Shirzad noted.

In the meantime, Qari Mutiullah Abid, the spokesperson for the Ministry of Energy and Water, said without going into further detail that for a number of decades, due to global climate changes, population density, economic, agricultural, and industrial activities, as well as other factors, the water level has been steadily declining, while the sources of water supply have become more scarce. Afghanistan is one of the most vulnerable countries in the world in this regard.

The spokesman added that while this issue has mostly been seen in the western, southwestern, central, and southern provinces, other regions of the country are not exempt from its detrimental impacts.

According to Abid, the Ministry of Energy and Water is dedicated to managing the country’s water supply and has implemented several projects in this regard. The work on some dams, including the Bakhshabad dam, is also ongoing. However, in most regions of the country, the balance of underground water is not equal.

Several projects have been carried out in the Qargha dam, and the water of the Paghman valleys, which was running from Kabul city, has been controlled, according to the information provided by this official of the Ministry of Energy and Water. Progress has been made in transferring water from Panjshir to the province of Kabul and the arbitrary drilling of deep wells has also been prevented.

Abed urged the citizens to avoid wasting water and dig absorption wells within their homes, which could be used to feed underground water and prevent water waste.

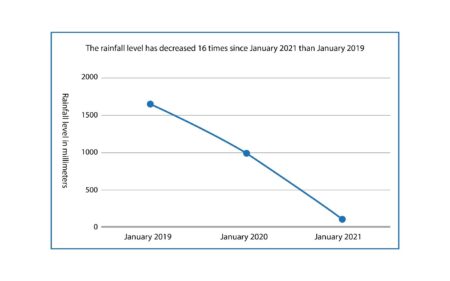

According to the Ministry of Agriculture’s annual report on meteorological for the solar year 1400, it rained in January 2019 with 1650.5 millimetres, in January 2020 with 993.89 millimetres, and in January 2021 with 101.63 millimetres. Based on these figures, the amount of rainfall in January 2021 was 16 times lower than it was in the same month in 2019.

In January 2019, there was no precipitation in the province of Nimroz, while there were 11.9 millimetres on average in the provinces of Helmand, Farah, Kandahar, and Nangarhar, and 55.2 millimetres on average in the other provinces.

In January 2019, there was no precipitation in the province of Nimroz, while there were 11.9 millimetres on average in the provinces of Helmand, Farah, Kandahar, and Nangarhar, and 55.2 millimetres on average in the other provinces.

The provinces of Baghlan, Nangarhar, Balkh, Bamiyan, and Samangan saw the least rainfall in January 2020; the average amount was 5.7 millimetres. The other provinces saw an average rainfall of 33.2 millimetres during this time.

In January 2021, there was zero precipitation in 15 of the nation’s provinces (Urozgan, Zabul, Farah, Daikundi, Nimroz, Kandahar, Ghazni, Parwan, Kapisa, Logar, Helmand, Kunduz, Ghor, Wardak, and Nangarhar), while there was an average of 5.3 millimetres of precipitation in the remaining provinces.

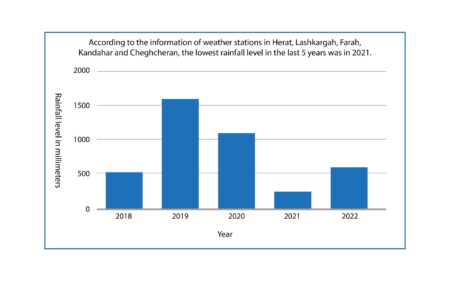

A report from the Afghanistan Meteorological Department, which was released on the 18th of the month of Jawza 1402 (solar calendar), indicates that the lowest rainfall in the previous five years occurred in 2021 at the meteorological centres in Herat, Kandahar, Lashkargah, and Firuzkoh.

According to the Afghanistan Meteorological Department, the average annual rainfall in the areas mentioned above was 540 mm in 2018, 1610 mm in 2019, 1110 mm in 2020, 260 mm in 2021, and 610 mm in 2022, on the basis of data from meteorological centres in those locations.

According to the Afghanistan Meteorological Department, the average annual rainfall in the areas mentioned above was 540 mm in 2018, 1610 mm in 2019, 1110 mm in 2020, 260 mm in 2021, and 610 mm in 2022, on the basis of data from meteorological centres in those locations.

Reduction of the Water Level

Twenty people from 10 provinces (Kandahar, Nangarhar, Balkh, Herat, Kabul, Baghis, Laghman, Khost, Parwan, and Baghlan) were interviewed to determine how much the water level has decreased in the previous five years. They say that the water level in the previous five years has decreased by an average of 11 meters, taking into account the decline in the water levels of the wells in their localities.

According to data from the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation, and Livestock, Afghanistan has 2.2 million hectares of agricultural land and 1.1 million hectares of rain-fed land, with 10% of irrigated land being irrigated with modern technology and the majority of irrigated land being dependent on monsoon rains.

According to data from the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation, and Livestock, Afghanistan has 2.2 million hectares of agricultural land and 1.1 million hectares of rain-fed land, with 10% of irrigated land being irrigated with modern technology and the majority of irrigated land being dependent on monsoon rains.

According to Afghanistan’s National Environmental Protection Agency’s (NEPA) second national report on climate change, which was released in Jadi of 1396 (solar year), spring rainfall in the country’s central highlands dropped by almost 40%. By 1429 (solar year), this department predicts a decrease of 5 to 10% in rainfall in the central and eastern highlands of the country.

Drought-Related Harm

According to Ruhollah Amin, head of climate change at the Department of the Environment, since 1329 (the solar year), the average temperature has gone up by 1.8 degrees, resulting in severe droughts, erratic rainfall, floods, and degradation of agricultural fields.

Amin said that during the past ten years, unseasonal rains and ongoing droughts have had a significant impact on agriculture. As a result of these droughts and floods, more than 100,000 hectares of agricultural land and around 46,000 hectares of gardens have been lost.

In the meantime, people in several provinces claim that their harvests have been reduced in half as a result of severe droughts in some areas and that in some places even farmers were unable to grow crops as a result of the drought.

One farmer in Helmand province’s Nad-e Ali region, Gul Mohammad, whose watermelon and melon harvests have been steadily declining for at least five years, said that this year he has no corps at all.

“We used to get 400 to 600 watermelons from an acre of land in previous years, but this year, due to the lack of water, we did not cultivate any,” Gul Mohammad said.

Abdullah from the Nahri Saraj district of Helmand Province also said that this year’s drought has left his agricultural grounds uncultivated and bare.

“We could not grow watermelons because of the lack of water, and if anyone did, their crops dried up because of the drought,” he said.

However, a recent report from the National Statistics and Information Authority (NSIA) shows that the amount of cultivated and arable land in the nation has grown by 7.7% as compared to the previous year.

NSIA spokesperson Mohammad Halim Rafe said: “The total area under cultivation in the 1402 solar year amounts to 2.8 million hectares, of which 2 million hectares are irrigated and 800,000 hectares are rain-fed areas. In comparison to previous years, this number shows a rise of 7.7%.”

A 50% Drop in Livestock

Alongside agriculture, livestock is an important sector that has seen a 50% decline in the past 10 years and a 25% decline in the past five years as a result of drought brought on by climate change.

According to the Environment Department’s second climate change report, the number of cows has fallen from five million to three million and that of sheep and goats from thirty million to sixteen million as a result of the country’s frequent droughts, which shows a 50 per cent decrease in livestock.

“Sadly, due to the droughts of the last few years, more than two hundred thousand livestock have been lost,” said Sader Azam Osmani, deputy minister of the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Livestock.

Abdul Ahed Qalil, the general director of natural resources for the Ministry of Agriculture, said that the lack of monsoon rains has resulted in the loss of grasslands and arable lands in the northern regions of the nation, leading to the loss and reduction of livestock.

“Due to the drought, the pastures in these areas have been entirely decimated, leaving livestock with nothing to eat. Even some owners of livestock have relocated their animals to grassier areas like Ghor. Some of these cattle owners have even been compelled to sell their livestock for extremely cheap prices,” he said.

The Displacement of People

The Ministry of Refugees and Repatriation’s (MoRR) spokesman, Abdul Mutalib Haqqani, said assessments by the ministry indicate that many residents have relocated to the districts and the centres of the provinces from the provinces of Nimroz, Farah, Ghor, and Herat as a result of recent droughts and water shortages.

According to Haqqani, in the last one year, 108 thousand people have been displaced from their main areas due to lack of access to water.

Residents in a number of districts have relocated to the centres of provinces, Nimroz being one of these provinces, due to a scarcity of water.

Abdul Aziz, 46, who moved from Sardasht village to the city centre as a result of not having access to water, said that the well water there was unclean.

The assessments of the State Ministry for Disaster Management, show that the current solar year’s drought has seriously harmed at least 20 provinces in the north, northwest, southwest, and centre of the country.

Among them, Herat, Farah, Nimroz, Ghor and Kabul are facing the biggest shortage of drinking water and drought.

Nisar Ahmad is a resident of Farah City’s PD 3. After his water well dried up last year, he now buys his drinking water from an ice firm.

Many nation residents, particularly those who live in the capital, are experiencing water scarcity issues as the water level continues to drop. They travel for hours to get the water they need from distant locations.

Bala Koh-e-Afshar’s residents are facing a serious water scarcity right in the centre of Kabul city. Second-grade student Qais, age 9, brings water from Bagh-e-Bala Mosque to his house in Afshar’s Bala Koh with his frail body after being let out of school in the hot sun.

In the meantime, Shafiullah Zahid, the director of Kabul’s water supply, said that 42 of the city’s 76 wells have dried up.

According to Zahid’s data, Kabul’s water supply system is designed to serve three million people. At the moment, 36 water wells are active within the city, serving 40% of the population while 70% of the homes in Kabul’s mountainous areas lack access to water supply services.

Zahid added that Kabul’s wells are the Logar project, Alauddin project, Chehel Dukhtar, and Ministry of Defense, and that water transfer projects from the Qargha Dam, Panjshir River, and Shahtoot Dam will soon provide Kabul with water.

What’s the solution?

According to Kabul University’s head of the Faculty of Environment, Professor Mohammad Daoud Shirzad, it is the obligation of the government and the people to collaborate to find a solution to this issue. Afghans will face a catastrophe if the government does not control water.

Shirzad urged people to conserve water and drill wells to store spent water so that it can seep back into the earth.

Another expert, Mirwais Khogyani, stressed the importance of switching from stream to drip irrigation and added: “Plants and trees that require less water should also be planted. Maintaining meadows, creating artificial glaciers to offset the harm caused by the melting of natural glaciers and their water variations, as well as helping to conserve water and stop deforestation, are crucial and extremely significant.”

However, Sayed Qayoum Hashemi, a specialist in environmental matters, underlined the need for surface water management in the nation to combat drought and prevent its effects.

“Considering the climate changes and ongoing droughts, water diversion dams must be constructed to address the concerns of agricultural and drinking water. Serious attention should also be paid to the feeding of underground water,” Hashemi noted.

In the end, it is important to note that the recent droughts and climatic changes have had a detrimental impact on livestock agriculture, and people’s livelihoods in general, requiring the need for substantial government action.

According to experts, people can also prevent excessive water use and contribute to the solution of the issue of water scarcity.

Follow TKG on Twitter & Facebook